london exhibition

Atsushi Kaga

your memorabilia floats in the air

Atsushi Kaga

your memorabilia floats in the air

9 October - 10 December 2022

A silenced record player, Jakuchū’s dancing, courting sparrows, the Daikon Buddha[i], widowed penguins, loads of bugs, twelve cats and some very large flowers…

The assembled ‘cast’ of foreground(ed) metaphorical objects/beings/surrogates, in Atsushi Kaga’s three large paintings that constitute his first solo show for mother’s tankstation | London, your memorabilia floats in the air, are indeed a diverse collection. Collectively, they engage sets of cultural and personal references, as well as indirect and unpredictable, intuitive observations. (Example: oh, [!] it would be so helpful if Swiss Air hadn’t lost my spectacles – along with all my best shirts and favourite shoes on a flight to Tokyo (my ephemera floats in the air). Aside: I mention this only (because I’m venting, but…), it’s an odd thing that while we were in Atsushi Kaga’s native home, Tokyo, sans luggage, Kaga was in ours (gallery/home), working hard, as he noted in an Instagram posting, “…like a medieval monk slavishly labouring over an illuminated manuscript…” (a sentiment accompanied by a moodily evocative moonlit nightscape of our neighbourhood Guinness world, beyond the gallery door). It’s not that Kaga-san doesn’t have his own home / studio to go to, or that we chain him up to work through the night – we’d never resort to anything quite that Gothic[ii] – rather, he is currently on a Dublin City Council residency in a very cute cottage in the edge of an elegant park and gardens (autocorrect just put in ‘elephant’ – which seems like it’s reading my mind, given Kaga’s recurring references to Jakuchū’s pachyderm. The point being, that it is a cottage (cute cottage = Romantically little, small doorways and windows, “Smokey chimney and narrow staircase”[iii]), which just necessarily doesn’t work so well for large format painting. It also just happens that our Dublin gallery was closed for the summer, that we had, aforesaid – long distance travels and that the opportunity was there for Atsushi to go large while we were going little. I’m sure there’s also some sort of latent comment, lurking like a medieval monk[iv], regarding cats and mice, but I just can’t chain it down right now.

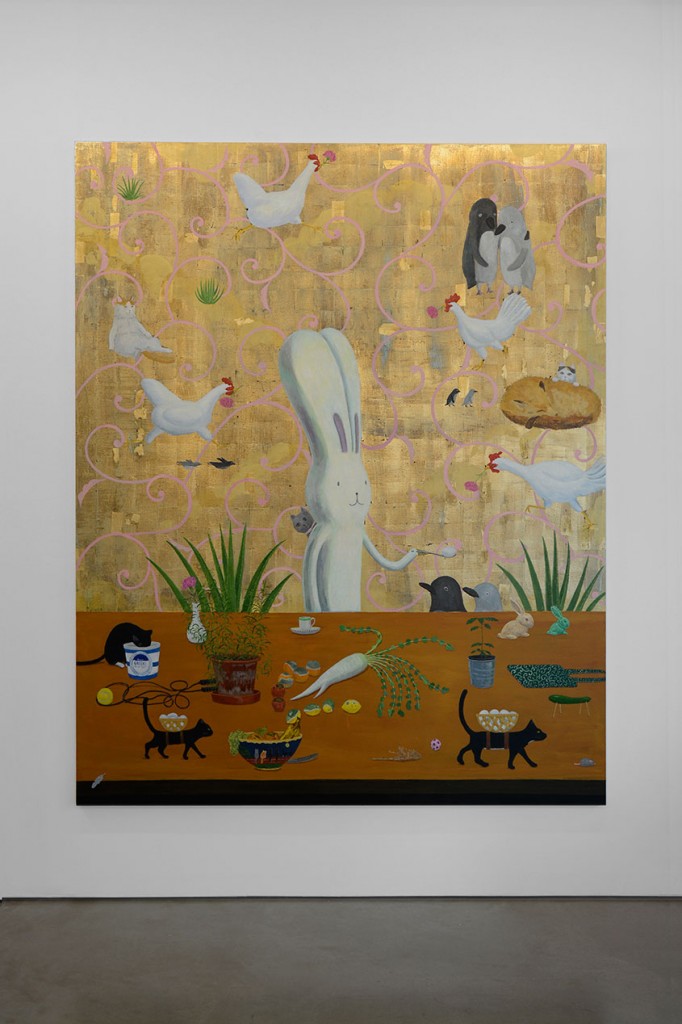

The mother’s tankstation | London gallery space is compact (bigger than a cottage however) and suits precisely focused projects, so rather than multiple small options, Kaga has privileged his favoured 210 x 170 cm format, allowing him an expansive scope of numerous small details, that allegorically combine and build complex associative narratives across the three paintings which follow Kaga’s now familiar compositional structure of an illusionistic table-top situated before an infinite/flattened rear space. Kaga’s gilded grounds, here all gold leafed, defy the rules of perspective and marry European Albertianism[v] to more traditional Japanese flattened decorative representations – complicated of course, by his adopted referrals to the Edo period spatial experiments and interventions of Jakuchū, Kuniyoshi and Hokusai (more later).

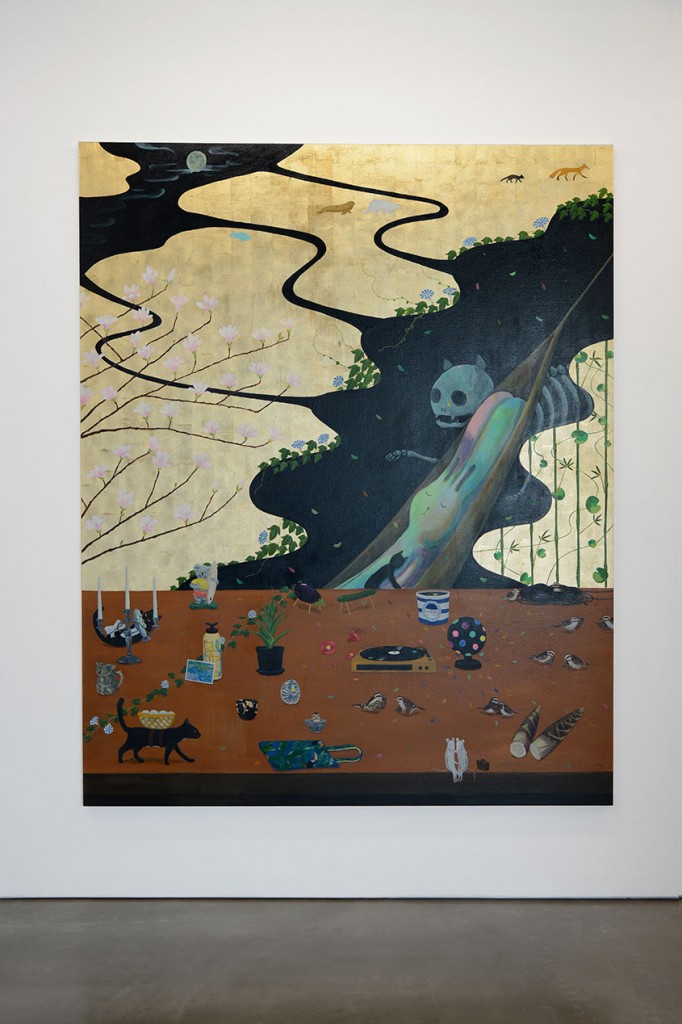

Usacchi, Kaga’s complex, iconic alter ego trickster rabbit ‘self portrait’ is at the centre of each painting, asleep and dreaming (kitten slumbering on chest) musing on the fragility of things (artist not cat), the unclear future perhaps; Usacchi loads eggs into baskets strapped to the backs of black cats… And in The last touch, tenderly reaches out to check in upon his perpetual friend, Kumacchi, as he drifts heavily towards a marijuana-induced slumber, the ghost pain finally gone from his amputated leg.

Curiously, while a Kaga-mouse in the cats’ home, a number of things, personal items, houseplants etc,. have ‘ghosted’ into Atsushi’s eye-line and therefore insinuated themselves into the paintings’ internal lexicon: washed-out yoghurt pots, intended for the recycling swag have become drinking receptacles for multiplicitous felines. Grandmother’s Deco ceramic rabbit ornaments are now making an orderly exit stage left in After you left, the two cats came into my life, (all works 2022), Finola’s maternally-bequeathed family candelabras sit unlit, half burntdown and spookily cold and dark, upon the Kaga table-tops. Some “difficult to paint” modernist German vases[vi] nestle, and fall into step with, or in unlikely companionship, beside painted references to classic Japanese Yakimono (literally ‘fired’ or ‘burned thing’) ceramics. And a plethora, a cornucopia, of vegetables and wildlife threaten a coup d’état of the whole damn lot.

Amongst the abundance of life in paintings one, two, three, death lurks aplenty, in the guise of Kaga’s perpetual Vanitas: eggplant and cucumber are each given four little wooden stick legs (like inserted matchsticks), in the traditional Japanese manner of funerary spirit horses and cows (shouryouma), placed outside a home after a family death. A disconnected record player also centre-ground in; Surrounded by memorabilia, becomes a quietly (literally) potent symbol for the show. Kazuko Kaga, Atsushi’s mother, mega-sewer and sometimes artistic collaborator (Nerd bag projects at the Irish Museum of Modern Art and Art Basel Miami Beach[vii]), purchased a record player with the intention of winding down to favourite LPs in quiet years, but the player never played as the years never quietened. The painting visually captures sound, projecting refracted disco lights into the silence of Usacchi’s dreams. Behind our sleeping protagonist hero, possibly an artist/cat/rabbit/vampire, lurks the darkened skeleton of a wild, in the untamed sense, kitten that Kaga rescued. Upon taking the tiny creature to the vet for necessary medical upgrades, shots, neutering etc, poor thing revealed as unexpectedly fragile and didn’t survive standard procedures, and now seemingly stalks and haunts Kaga’s dreamspace, like Kuniyoshi’s Takiyasha The Witch and The Skeleton Spectre, and Raikô Dreaming of the Earth-Spider with Demons, from his 1843 allegorical graphics[viii]. Interestingly, Timothy Clark, curator of Japanese art at the British Museum, has noted that the Tenpō Reforms[ix] of 1841-3, aimed to alleviate a socio-economic crises (not unlike our present own…) in Japan of the time, by placing restrictions on the depiction of public displays of luxury, wealth and privilege. It’s hard not to think of the UK teetering on the edge of economic disaster/chaos by self-inflicted wounds, while visually distracting itself with bombastic pomp and ceremonies. The hard realities remain behind a highly-coloured-curtain – ‘Trussonomics[x]’ lurk like the Kuniyoshi spider – The Tenpō Reforms drove artists like Kuniyoshi, towards more abstruse forms of polemical commentaries, similarly the currency and piquancy of Kaga’s pictorial references should not be underestimated…

As ever within Kaga-world, the fragility of boundaries between loneliness, hermeneutics to companionship and the necessity of ‘human’ contact, of course tangentially expressed by Kaga through the narrative of invented animals/mythic characters, occupies central territory at his pictorial table. Upon which, Jakuchū’s sparrows perform ritual courtship dances towards one another, bowing, flamboyantly showing extended wingtips, towards the hope of love and filial partnership. Likewise, insects display their gaudiest jewel-like finery… Kaga has also borrowed the allusion of the Melbourne penguins[xi]; who (is that correct?) appeared – in a social media moment during the height of the globally-shared-loneliness-of-lockdown (December 2020) – evidently to find platonic comfort in each other following respective partner loss. Similarly, pair of mice embrace, as one of the loving couple seems destined for distant travels, suitcase packed and waiting at their feet/paws/claws. Long-distance relationships are hard even for tiny rodents.

Knowing and loving Atsushi Kaga’s work for many years now, since he was student at the National College of Art and Design, Dublin, where and while he studied, the boundless wealth of imagination has been a constant marvel. From his informal panel paintings and looser coloured crayon maker drawings, animations and poignantly engaging small sculptures, to the more formally articulated canvases of recent years, his sense of invention has never skipped a beat. But continues to inspire delight (ours at the very least) in the fact that the more his practice becomes globally known, it’s appreciation seemingly transcends nationhood, culture, class, hard and soft sells of aesthetics, finding approbation from devotees of brutalism, minimalism to the most rococo kitsch. All unexpectedly finding commonalities of empathy in Kaga’s meta-negotiation of ‘Kawaii’[xii]. Atsushi Kaga’s work is of course quintessentially not cute (underscore), but employs all the soft-power strategies and tactics of loveable cuteness to negotiate darker territories. We have explored some of this ground in previous texts and I redirect you to these [xiii], so not to reiterate but rather refer. To summarise however, Kaga enfolds the dialectical psychodrama of the philosophical encounter with the everyday, into his daily-sustaining sandwich, bread and butter, meat and mustard… place your order here for click and collect…

Diegesis[xiv], an idea embedded in narrative theory, that posits that a central protagonist, a ‘narrator’ or a subject at the epicentre of a story – here not unlike Usacchi – and describes and explains them via exterior voice/s, a multi-phonic reverberating ‘chorus’ in Ancient Greek theatre (is there anyone out there, out there…..), that elaborately embroiders associated, or embellishing threadlike tales around the core motif; overheard telling and re-telling perhaps, shifting the footing from first person to third, fifth, person perceptions, and back again. From which, an audience builds a seemingly ‘privileged’ perception of things, that the protagonist specifically may not be privy to, see or know. I heard that …The enemy is an hour away from the outer walls… We, the audience thusly (private joke), occupy the privileged possession of ‘truth’. “It’s behind you!!!!”

Kaga seems implicitly to understand this, a concept now made most brutally evident in the ‘meta-truth’ of social media – wherein we appear to see and know every thing about everybody, all at a glance, all at once, all the time. This ‘truth’, however may not be that ‘true’, but the contemporary contrapuntal understanding of such would give us the dubious concept of ‘personal truth’, my truth,…i.e., I believe it to be so, therefore GFYS… which is not unlike, the theoretically privileged narrative ‘truth’ in diegesis. There’s a term in Latin; amplissium terrarum tractum, that embodies this, which is an idea that derives in the story of the satanic temptation of Christ, to see and ‘know’ all from the highest mountaintop… everything all at once, all of the time. Where does this lead us, apart from down the primrose path? Coming back to Jakuchu, Kaga inherits the super-facility to embody ‘things’, all things, all at once’; exemplified in the Daikon Buddha (which appears not once but twice in the exhibition[xv]), soft bears become all misfortune, a rabbit with extraordinary human traits transforms the artist into anything they want to be, dream of, and/or therefore say, without restriction, within and without restraint. The transformation of things, all things, that blind us, the things that bind us…

[i] Ito Jakuchū (1716-1800), the son of a grocery family and a one-time grocer himself, painted a funeral scene portraying the dead Buddha as a radish surrounded by mourning vegetables. (seriously) … Suzanne Muchnic notes in her 1990 Los Angeles Times article: “There’s a certain logic to Vegetable Parinirvana, the improbable and apparently irreverent death scene. Ito Jakuchū was the son of a greengrocer and ran the family’s wholesale business for 17 years before he became a full-time artist at 40. He may have been more at home with the mushrooms, persimmons, yams and cucumbers in his parody than with human characters. An assiduous observer of nature, Jakuchū also raised chickens and elevated them to lofty heights of grace and beauty in his paintings”. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1990-01-01-ca-30-story.html

[ii] Kaga, however seems suspiciously nocturnal, so he may in fact be half cat, half vampire. Gothic enough?

[iii] Jane Austen, Sense and Sensibility.

[iv] ibid no.ii

[v] In 1435 the Italian humanist and artist, Leon Battista Alberti wrote a treatise entitled De Pictura (On Painting), in which he outlined a process for creating an effective painting through the use of one-point perspective. Investigation of the mathematical concepts underlying the rules of perspective led to the development of a branch of mathematics called projective geometry.

[vi] Gerhard Barbeit 1960s’ ceramic in the front of; The last touch.

[vii] Nerd bag, Irish Museum of Modern Art, 2010: http://www.motherstankstation.com/exhibition/atsushi-kaga-nerd-bag/overview/

Nerd bag factory, 2012: http://www.motherstankstation.com/exhibition/art-basel-miami-beach-2012-art-positions/overview/

[viii] Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861). Associated with the Utagawa school, the range of Kuniyoshi’s subjects included many genres: landscapes, beautiful women, famous actors, cats…, and also not-unlike Kaga, more mythical animals.

[ix] The Tenpo Reforms of 1841–1843, aimed to alleviate economic crisis by controlling public displays of luxury and wealth, and the illustration of courtesans and actors in ukiyō-e was officially banned at that time. This may have had some influence on Kuniyoshi’s production of caricature prints or ‘comic pictures’, which were used to disguise actual actors and courtesans. Many of these symbolically and humorously criticized the shogunate – the hereditary military dictatorship of Japan (1192–1867) – such as the 1843 designs, mentioned above, showing the famous actor Minamoto no Yorimitsu, like Usacchi in ‘Surrounded by your memorabilia’ asleep, haunted by the Earth Spider and demons. Such works became popular among the politically dissatisfied public.

[x] A short-lived phenomena for which the present British Prime Minister may become famous for all the wrong reasons: Simon Jenkins, Trussonomics has been exposed as childishly absurd. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/sep/29/trussonomics-liz-truss-kwasi-kwarteng-economic-crisis

[xi] Widowed penguins hug in award winning photo: https://www.bbc.com/news/in-pictures-55416365

[xii] In Japanese, the word literally means “acceptable for affection” or “possible to love” and has been obliquely translated as meaning “cute,” “adorable,” “sweet,” “precious,” “pretty,” “endearing,” “darling,” and even “little.” …

[xiii] Previous Kaga texts: http://www.motherstankstation.com/exhibition/happily-skipping-backwards-2013-1978/text/

[xiv] Specifically, diegesis is a style of fiction storytelling that presents an interior view of a world, in which: (a) Details about the world itself and the experiences of its characters are revealed explicitly through narrative. (b) The story is told or recounted, as opposed to shown or enacted. (c) There is a presumed detachment from the story of both the speaker and the audience.

In diegesis, the narrator tells the story, presents the actions (and sometimes thoughts) of the characters to the readers or audience. Or course we, the audience, are given insinuated choices, as to how much we ‘trust’ the narrator and therefore the veracity of third-party+ narratives

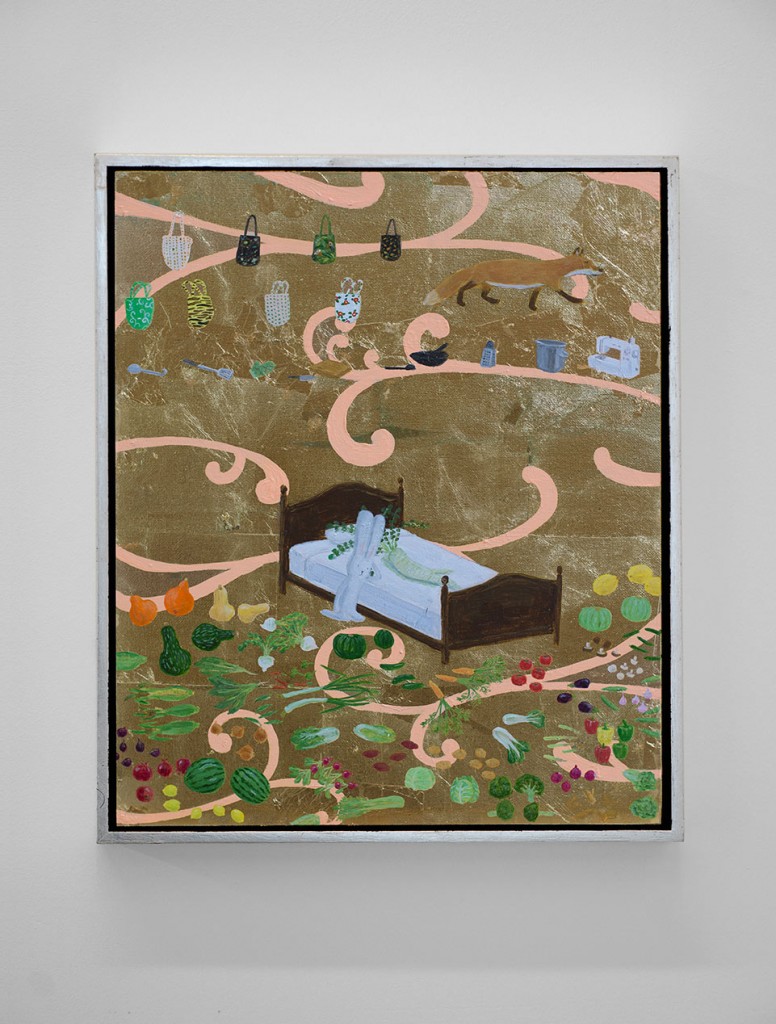

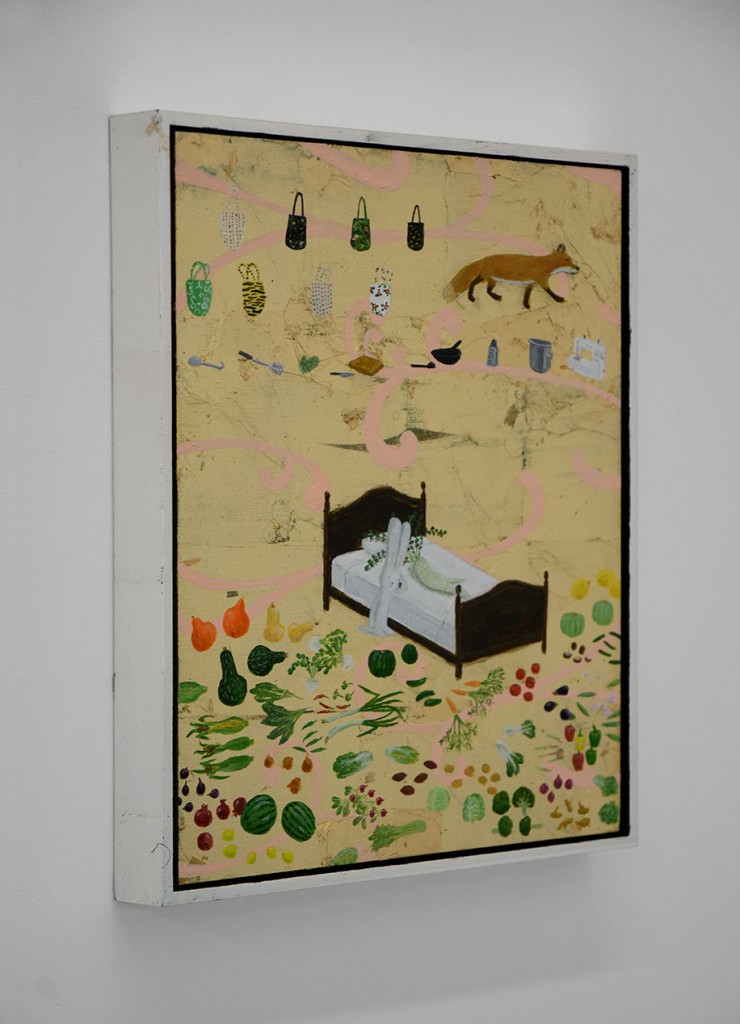

[xv] The Daikon Buddha, makes appearances in the large painting, After you left, two cats came into my life – surrounded by a funerary party of rotting lemons. And in the small panel painting, Your memorabilia floats in the air, which gives the show it’s title. In this instance the Daikon is prone on a bed, before which Usacchi sits and mourns, surrounded by a floor of vegetables. Kazuko’s ‘nerd bags’ float in the air above, and her fox spirit exits stage left.